The metastatic cancer challenge

One in two of us will be affected by cancer in our lifetimes, with one in four dying within 10 years of diagnosis. But often, that initial lump is not responsible for our ultimate demise. So why are we not doing more to tackle the actual causes of mortality in cancer patients? Our Director of Oncology Drug Discovery, Dr Allan Jordan, explores further…

Cancer is almost universally regarded as an insidious disease, gradually growing inside the body until eventually causing death. But, perhaps surprisingly, this outcome is not necessarily inevitable or unavoidable, and the reality is often quite different. Cancers actually grow rather slowly, only barely outgrowing the tissues and cells around them. In fact, growth is almost imperceptible in the early stages, making early diagnosis very difficult and also meaning it can take decades before a tumour makes its presence felt.

But even at this advanced stage, many tumours remain benign, self-contained and of limited burden. Prostate cancer is one example of this, with many men (perhaps up to one in three) dying with (and not from) prostate cancer after living blissfully unaware of the unwelcome growth except, perhaps, for a little extra difficulty in going to the loo. Many other cancers will also form small, discrete tumours but remain limited by access to nutrients, oxygen and other resources – effectively held in a state of perpetual limbo by the body’s own checks and balances.

Some of these tumours will eventually become bothersome, exerting pressures on various organs and leading to symptomatic disease. Often, surgery can be curative, removing enough tumour for any residual cells to be unable to create a large enough tumour to become problematic before the patient passes away through old age.

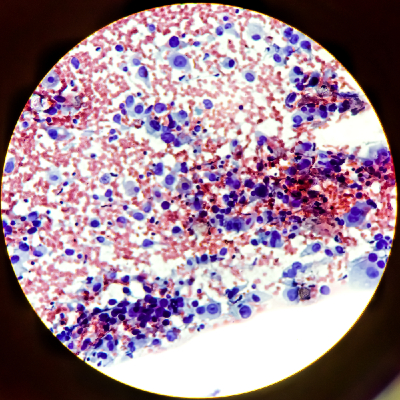

These benign tumours are not the biggest killers. Unfortunately, many tumours are less well constrained and become invasive, metastasising through the body, infiltrating key organs and leading potentially to multiple organ failure and death.

This invasive spread, and the trail of biological devastation it causes, is the real reason behind most of our cancer deaths.

The hurdles before us

We’ve known that metastatic disease is responsible for most cancer deaths for decades. So why, even now, are we not treating invasive disease more successfully?

To some extent, we do treat this widespread disease – our arsenal of cytotoxic chemotherapy agents are dosed systemically and impact many of these metastatic sites. Gruelling as they are, they remain our best line of treatment for disseminated disease and secondary tumours.

But why are we not better at treating patients earlier, before their primary tumours spread and while treatment may be curative? It’s a noble goal, and many cancer researchers have dedicated decades to understanding the process of invasion and metastasis in the lab in the hope of being able to prevent this in patients. But in the world of real patients, it’s much more complex, and ultimately distils down to three key factors:

1. Late diagnosis

While detection techniques are improving all the time, most patients are diagnosed relatively late in the history of their cancer’s growth. We’re increasingly aware that early invasion, to form small, semi-dormant micro-metastases, often occurs very early on the development of cancer – years, if not decades, before diagnosis. A drug to target this process would therefore be dosed too late for benefit if used at the time of diagnosis.

2. Drug safety

The natural response to the above challenge is to dose at-risk patients (or a wider population) much earlier, before metastasis is present. This idea of prophylactic treatment for cancer is appealing, but carries its own risk. As all drugs have side effects, it would be a difficult argument to dose wide (and often younger, likely healthy) populations with an anti-metastatic drug without being able to quantify the risk-benefit relationship and understand who may be at risk. Indeed, prior trials of drugs in similar preventative settings have led to the identification of idiosyncratic side effects in these younger populations and resulted in drugs being withdrawn from the market, ultimately reducing options for patients.

3. The challenge of trials

Even if a way was found to identify pre-metastatic patients, the demonstration of efficacy required to bring a drug to market would remain a significant challenge because metastatic disease can take decades to become evident, and patients would need to be monitored regularly over this time to see if an effect was evident. Multiple additional risk factors and lifestyle choices would need to be fully accounted for, requiring significant numbers of patients on trial to be sure the data were robust and meaningful.

Such a trial would be complex, time consuming and eye-wateringly expensive, and it would be many years before any patient benefit became evident.

Such a trial would be complex, time consuming and eye-wateringly expensive, and it would be many years before any patient benefit became evident.

This kind of trial complexity is probably the single biggest challenge to the delivery of a preventative treatment for metastatic cancer. It’s quite telling that, after perhaps half a century of research, not a single drug has ever been shown to be effective at preventing metastasis in patients.

“It’s telling that not a single drug has been shown to be effective at preventing metastasis in patients.”

New approaches – and possibilities

But perhaps the future for patients with secondary disease is not as bleak as it appears. Maybe we have been looking at this aspect of cancer from the wrong end of the process. As we better understand the relationship between the disseminated tumour and its underlying tissues (the “metastatic niche”), it’s becoming clear that we may have some of the tools to address this issue.

Our recent immune-oncology agents can reprogramme the immune response in this niche to make the environment more hostile toward the invading tumour, while specifically targeted therapies offer the promise of better-tolerated systemic treatments, particularly if they can penetrate into hard-to-reach metastatic sites such as the brain.

So it’s possible our next advances will come from a better understanding of the complex interplay of these established tumours with the body, and not from their formation in the first place. Could we have been looking at the wrong end of the cancer timeline? Perhaps a change in our viewpoint heralds a new frontier for the delivery of better drugs to treat the longest standing issue in cancer treatments – the peril of metastatic disease.

Indeed, it may be that only by looking at cancer from new angles and from different perspectives will we achieve greater success in really tackling mortality (while also striking the balance of maintaining a high quality of life for patients).

Indeed, it may be that only by looking at cancer from new angles and from different perspectives will we achieve greater success in really tackling mortality (while also striking the balance of maintaining a high quality of life for patients).

That’s something we’re passionate about at Sygnature Discovery, and why we work across the entire span of oncology drug discovery. In fact, I recently published a paper in the British Journal of Cancer on the need for greater collaboration between drug discovery scientists and their clinical colleagues.

By working in integrated teams made up of specialists in medicinal chemistry, DMPK, bioscience and in vivo translational oncology, we’re better able to build a collective knowledge base and share best practice, ideas and experiences.

And with new perspectives, different ideas and a more collaborative, integrated approach to drug discovery, the future certainly looks a lot more exciting.

Interested in oncology? We love talking about it. Get in touch with us to discuss your project or challenge, or watch our webinar on how oncology drug discovery could be made better.