Reducing clinical risk with earlier drug discovery toxicology

We undertake a detailed risk assessment for every experiment we perform in the lab, but rarely undertake the same rigor for our projects. Pivotal to this approach, toxicology studies should be a routine part of risk assessment right from the early stages of drug discovery, say Allan Jordan, Director of Oncology Drug Discovery here at Sygnature, and Clare Sadler, a toxicologist with our expert collaborators Apconix.

There is a common perception that toxicology is merely one of the final hurdles that must be overcome just before an investigational drug starts clinical trials. If these late studies identify issues, then the resulting delays to the project can be significant.

There is a common perception that toxicology is merely one of the final hurdles that must be overcome just before an investigational drug starts clinical trials. If these late studies identify issues, then the resulting delays to the project can be significant.

Yet once a molecule enters the preclinical phase, chemists and biologists have already built an intrinsic set of properties into the molecules. These are largely fixed, and preclinical scientists are then left with the task of mitigating any risks and liabilities the molecules may have. This takes time, and may prove impossible.

Yet once a molecule enters the preclinical phase, chemists and biologists have already built an intrinsic set of properties into the molecules. These are largely fixed, and preclinical scientists are then left with the task of mitigating any risks and liabilities the molecules may have. This takes time, and may prove impossible.

We believe that drug discovery scientists should be thinking about risk assessment and toxicology much earlier than this, as we’re more likely to make good decisions about which molecules to progress if the potential risks are better understood. Rather than remaining a late-stage hurdle, toxicology should become a standard part of the drug discovery process, right from first identifying the target, through hit-identification and lead optimisation stages.

Understanding the potential liabilities a putative hit series carries may lead us to make different decisions about what molecules to take forward, or help build the cascade to more holistically optimize the molecules. Normally, we would choose a molecule because it has the best activity in an assay, and maybe also consider how easy it is to make. But this does not mean we have chosen the molecule with the highest probability of success.

Drug discovery toxicology should be used to evaluate both the inherent risk of the molecule and its intended target. In oncology, for example, toxicity seen in the clinic may involve primary target modulation, and therefore may be unavoidable. However, if we can understand the role of the target in normal physiology and therefore the potential adverse effects associated with its modulation from the beginning, we can build understanding on ways to mitigate these concerns. For example, understanding whether intermittent dosing still maintains efficacy but reduces toxicity. Or thinking about how the drug is likely to be dosed, as this may fundamentally affect the design of the molecule and its properties.

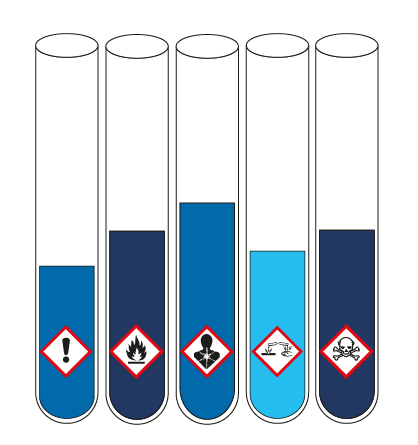

Off-target liabilities, where the molecule has another biological activity unrelated to the drug’s mechanism of action, can also prove problematic. Many such toxicities prove inherent to a chemical series. However, medicinal chemists can modify the molecular structure as part of the design process to avoid hitting off-targets, if toxicology understanding indicate they may occur.

When designing a molecule, we should be looking in more detail at off-target profiles, ion channels, secondary pharmacology, and even cytotoxicity assays. All of these will help us gain an understanding of how far away from a good quality drug candidate we are. However, many of these questions are frequently not addressed until the putative candidate molecule has been decided. By then, solving arising problems can often prove exquisitely difficult and risky to overcome and bring significant delays and increased costs at this later stage.

There are many issues to navigate through within a drug discovery and development process. The better the quality of the molecules, and the better the understanding of the target, the easier and quicker the path to market will be. Within the long and expensive clinical phase, anything that can be done to reduce the burden on the patients in terms of monitoring or adverse effects, is incredibly impactful.

This does not necessarily mean an increase in the lab work required – it’s about asking the right questions early on, and designing the right experiments. While some drug discovery activities have, to a great extent, already moved in this direction, this proactive approach is not standardly done.

If asking questions on the potential safety liabilities early was more routine, higher quality molecules would be taken forward, and molecules with fundamental problems would be far less likely to progress. While it might slow down the early lead discovery process slightly, the overall path to a safe, effective molecule should be shorter, and the process of clinical evaluation should be both more efficient and carry less risk of unexpected toxicities. Taken together, these quality improvements will, we believe, ensure that better quality drugs become available for patients more quickly.

If you enjoyed this piece, then you may find other topics in our (Re)thinking Drug Discovery range of articles of interest. Finally, we continually engage with our industry on a range of drug discovery topics. If you would like to discuss drug discovery, our capabilities or what we are about then we’d love to hear from you. You can get in touch by using any of the contact forms.