Psychedelics, a new frontier for mental health treatments

For cultural reasons, psychedelics have had something of a bad reputation. But over recent years research into these compounds has been steadily growing, revealing exciting possibilities in the field of mental health treatment. So what is the future of psychedelic research, and is it worth pursuing?

Author: Mike W Conway, Senior Scientist

A Brief History of Psychedelics

Psychedelics are a class of psychoactive substances that produce changes in perception, mood and cognitive processes via serotonin (5-HT) 2A receptor agonism[1], and have been used for millennia for their apparent healing powers, in rituals, and recreationally.

The term psychedelic was first coined by Dr Humphry Osmond and comes from the Greek terms “psyche” (mind) and “deloun” (make visible or to reveal).

During the 1950s psychedelics were used for a short period in the fields of psychology and psychiatry as aids to psychotherapy, as well as for treating alcohol addiction.[2] However, they quickly became negatively associated with the “hippie” culture of the sixties – youth rebellion, social upheaval and political dissent – and in 1970 President Nixon signed the Controlled Substance Act, going further in 1971 by declaring a “war on drugs”.

The Controlled Substance Act outlined five “schedules” that are used to classify drugs for their medical applications and potential for abuse. Schedule 1 drugs are defined as drugs with no current accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Marijuana, LSD, Psilocybin, Heroin, MDMA and other drugs are included on the list of Schedule 1 drugs.

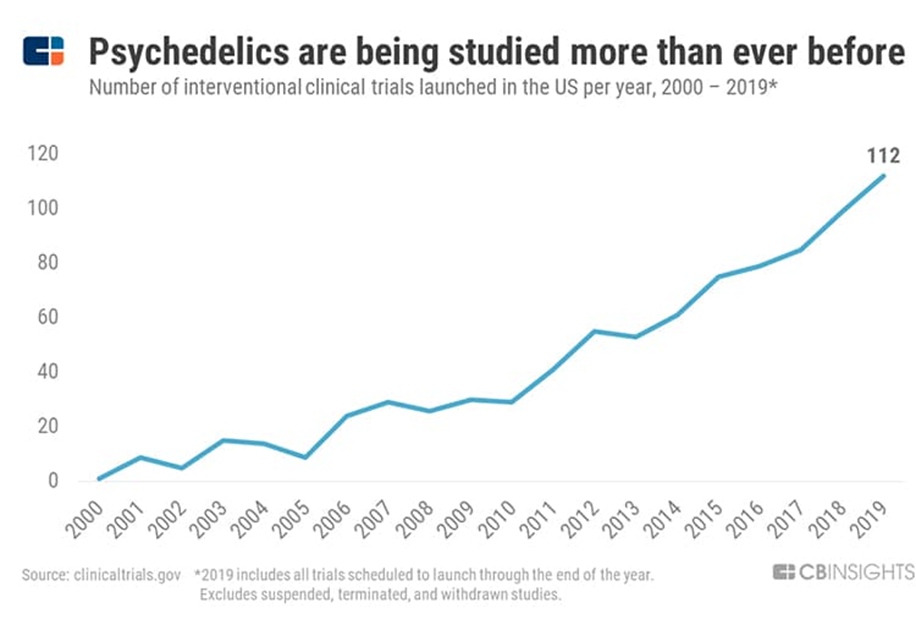

The legislation driven by the Nixon administration did not ban research on Schedule I substances outright, but the restrictions and significant requirements it introduced had the effect of discouraging scientists and clinicians from attempting to conduct research on Schedule I substances, or even applying for funding for such research. Despite these restrictions, psychedelic research did continue on a smaller scale, and began to build pace again from the 1990s.

Psychedelics and Mental Health

Today the world faces an expanding mental health crisis. The NIMH (National Institute of Mental Health) in the USA estimates the total costs associated with serious mental illness, which affects around 6 percent of the adult population, to be in excess of $300 billion per year.

Sadly, over recent decades there has been little or no significant breakthrough in the field of mental healthcare regarding more effective treatments for diseases such as treatment-resistant Schizophrenia (atypical antipsychotic Clozapine, 1974) and depression (SSRI, Prozac, 1987), leaving a significant mental health treatment gap.

Sadly, over recent decades there has been little or no significant breakthrough in the field of mental healthcare regarding more effective treatments for diseases such as treatment-resistant Schizophrenia (atypical antipsychotic Clozapine, 1974) and depression (SSRI, Prozac, 1987), leaving a significant mental health treatment gap.

What could psychedelics offer this field?

Psychedelics may have therapeutic roles in a range of psychiatric and neurological conditions due to their potential to stimulate neurogenesis, provoke neuroplastic changes and reduce neuroinflammation.[3] A growing body of research indicates that due to the positive psychological after-effects of a psychedelic treatment (improved mental health and psychological wellbeing), psychedelic therapy could potentially help millions of patients suffering from numerous mental health issues ranging from depression to eating disorders[4].

Proponents of psychedelic therapy suggest a comprehensive treatment package that involves highly trained and experienced clinicians who will monitor the patient throughout the experience as well as conducting follow up sessions offering advice and support. Though currently illegal in the UK and many other nations, some countries are forging ahead, and the world’s first legal, psychedelic depression treatment centre has recently opened in the Netherlands, using truffles containing psilocybin to treat patients who are battling depression and other mental health issues such as alcohol and tobacco addiction.

The Future of Psychedelic Research

Despite their therapeutic potential, many psychedelics are listed as Schedule I drugs by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), among others, due to their abuse risk and lack of current medical use. Their use is also restricted in the UK, China, Australia, New Zealand, Turkey, and several European countries.

However, with increasing interest and an improved understanding of the clinical benefits of these molecules, either alone or in conjunction with existing therapy, there is now growing impetus for a change in legislation that would facilitate this research in different regions and address the huge potential that this class of compounds can offer.

As the discipline of psychedelic research sheds its negative associations and moves into the mainstream within the scientific community, its presence has grown significantly in the search for new and more effective treatments for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, as well as for mental health issues such as treatment-resistant depression, PTSD, OCD, substance abuse, chronic pain and even end of life care.

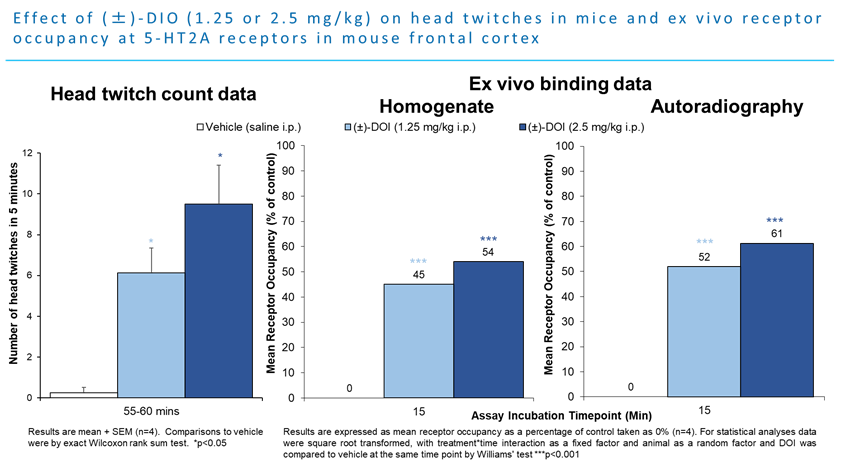

In recent years, the focus has been on studies involving psilocybin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and the role of 5-HT (serotonin) receptors, especially 5-HT2A. In both rats and mice, the head twitch response is a well-documented screening assay sensitive to the activation of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.[5] Using the selective 5-HT2A receptor agonist DOI, scientists at RenaSci (now part of Sygnature Discovery) saw a significant increase in the number of head twitches (here looking at the final five minutes) sixty minutes post dose at both 1.25 and 2.5mg/kg as well as increased receptor occupancy at both doses.

There are increasing reports of cognitive benefits from micro-dosing with these drugs[6] as well as numerous planned clinical trials. Research has shown that micro dosing with LSD can increase the levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) 4-6 hours post treatment. Decreased levels of BDNF are associated with neurodegenerative diseases with neuronal loss, such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis and Huntington’s.

The psychedelic drugs market is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 16.3% over the next eight years to reach $6.85 billion by 2027, according to Data Bridge Market Research, with the growing acceptance of psychedelic drugs for the treatment of treatment-resistant depression and other mental health issues.

While research into these compounds has been limited by the legislative situation, what has made it through the pipeline indicates exciting possibilities ahead and has slowly been working to shift attitudes across the globe. In addressing the mental health treatment gap we face today, the potential of psychedelics is clearly something that should be explored.

To discover Sygnature’s significant pre-clinical expertise in this area or talk to a scientist, click here.

[1] Juan F Lopez-Gimenez 2017, “Hallucinogens and serotonin 5-HT 2A receptor-mediated signaling pathways”.

[2] Robin L Carhart-Harris, 2017 “The therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs: Past, present and future”.

[3] Calvin Ly et al. 2018 “Psychedelics promote structural and functional neural plasticity”

[4] M.J. Spriggs et al. 2020 “Positive effects of psychedelics on depression and wellbeing scores in individuals reporting an eating disorder”.

[5] Olga Zhuk et al. 2015, “Research on acute toxicity and the behavioural effects of methanolic extract from Psilocybin mushrooms and Psilocin in mice”

[6] Lindsay P. Cameron et al. 2019 “Chronic intermittent microdoses of the psychedelic N,N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT) produce positive effects on mood and anxiety in rodents”