From Dinosaur Heresies to Neuroplastogen’s

Sometimes things need shaking up. When I read Robert Bakker’s book the ‘The Dinosaur Heresies’ I was hooked, although my dinosaur bone-digging career did not take off. Here was this book turning everything upside down that schoolbooks were espousing about dinosaurs being cold blooded, lumbering, inefficient, not very intelligent creatures. Well, there has been a lot of scientific research since, and even movies……and now we know! It’s not that dissimilar to lazy adages about the brain from the past – its fixed once fully developed, we only use 10% of the brain, etc. Maybe that’s an unfair comparison as there have been plenty of interesting ideas from the East and West about the brain, skull, and awareness of personality, psychological state, effect of prayer on the mind.

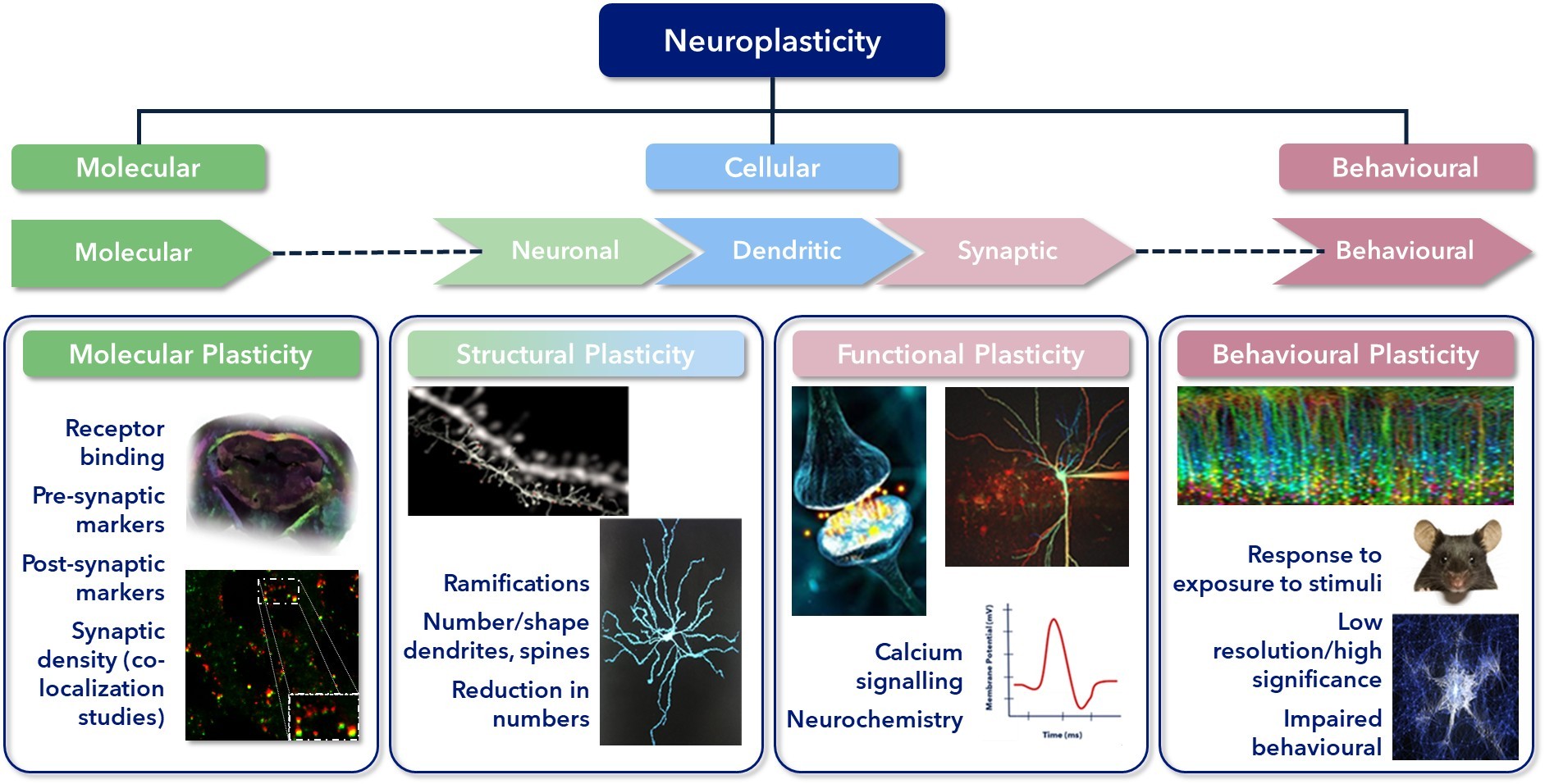

Today we know a whole lot more. We know that neuroplasticity is normal brain function in response to the external and internal environment, in development, in adulthood, and in disease. This has led to increased interest in psychoplastogen’s – molecules that can rapidly invoke long-lasting beneficial effects in psychiatric (depression, PTSD) disorders, and potentially in a range of other disorders: pain, cluster headache, addiction, anxiety, cancer related anxiety/dysphoria, post-partum depression, eating disorders, and in traumatic injury. How? – by inducing molecular, structural and functional neuroplastic changes in the brain.

The psychoplastogen molecules in question primarily include dissociative anaesthetics, psychedelics, and empathogens, although there are others. Indeed, JnJ’s Spravato® (esketamine) is a dissociative anaesthetic that has been shown to induce neuroplastic brain changes and is approved for treatment resistant depression as an add-on to oral antidepressants or as monotherapy. However, Spravato® is administered under supervision and patients must remain supervised by health staff for two hours. What’s more maintenance treatment on Spravato® is burdensome and frequent (2/week for the first 4 weeks, 1/week for weeks 5-8, and then 1/week or 2/week after week 9), amounting to 56 separate sessions or 112 hours of treatment time per year. Despite these real-world limitations, Spravato’s annual sales are >$1B and growing suggesting patient willingness to endure given the high unmet need.

With psychedelic and empathogen drug development we are seeing some encouraging Phase 2 & 3 clinical data emerging, innovation in clinical trial design, commercial pricing & infrastructure models being considered that lean-on and potentially improve upon Spravato’s®, a plethora of chemical matter being explored, some exciting fundamental science, and significant deals including big Pharma stepping into the mix (reference Abbvie-Gilgamesh and Otsuka-MindMed deals).

Clinical Data Highlights – by the time this goes out it’ll be out of date, but here goes!

Completed Phase 3 clinical trials include:

- Compass Pathways has reported a significant effect on the primary endpoint in the first of two Phase 3 trials assessing a proprietary formulation of psilocybin in Treatment Resistant P3 COMP360 reported significant (1, 2).

- Lykos therapeutics assessed MDMA in patients with PTSD showing it significantly reduced symptoms in 2 Phase 3 trials (3), but given some trial irregularities the drug was not approved by the FDA and another Phase 3 trial is necessary (4).

However, behind are a slew of companies (e.g., Cybin, GH Research, Gilgamesh, MindMed, Reunion, Atai/Beckley Psytech, Usona, Inncanex) that have successfully completed Phase 2 clinical trials in a range of different disorders (e.g., MDD, TRD, fibromyalgia, GAD, PTSD, anorexia nervosa, SUD, AUD, BPD, PPD).

The most common psychedelic/empathogen molecules utilised in Phase 2 trials are based on synthetic and chemically modified versions of Psilocybin, DMT, LSD, and MDMA, and the route of administration utilised is varied (e.g., IV, SC, intranasal, inhaled, IM, oral, sublingual thin film). The variety of chemical modifications (deuterated, pro-drug) and RoA approaches point to the importance of commercial drivers (including IP) and attempts to improve market adoption and therefore reimbursement.

Spravato® has led the way and defined codes for reimbursement that include cost of patient evaluation & prescribing, cost of drug itself, and cost of the treatment session (including medical staff time) in registered clinical centres. However, beating Spravato® on the basis of frequency of dosing, durability of efficacy, quicker dissipation of psychedelic AEs and monitoring time by medical staff, are all important factors that will impact number of visits to clinical centres, time spent in these centres by patients, and overall improve market adoption/reimbursement. Another factor that needs to be considered, at least for some of the current crop of clinical stage drugs is whether psychotherapy is an integral part of treatment as this will add cost pressure and considerations regarding commercial viability.

Of the most utilised psychedelic/empathogen based molecules being assessed in mid-to-late stage clinical trials Psilocybin, LSD and MDMA have longer half-lives than DMT suggesting DMT-based drugs might lead to shorter clinic visit times in the range of 1.5-3 hours, whereas treatment with the former drugs would require in the range of 6-8 hours per clinic visit, ie., a whole working day. However, this needs to be offset by durability of efficacy: currently, data would suggest that Compass’ COMP360 (psilocybin) and MindMeds MM120 (LSD) have sustained efficacy for up to 12 weeks after a single dose which equates to only 4 annual clinic visits. These commercial drivers emphasize that drug discovery teams need to have a good grasp of and innovative mindset to medicinal chemistry and DMPK disciplines.

Although there is debate as to whether the subjective experience (psychedelic, empathogenic, other) is important for the therapeutic efficacy of psychoplastogen’s, there are range of companies focussed on non-hallucinogenic or non-mind-altering approaches – so-called neuroplastogen’s. These molecules like psychoplastogen’s are argued to lead to molecular, structural and functional neuroplastic changes that underlie therapeutic benefit but without the subjective experiences imparted by the former class. The clear advantage would be that these molecules if approved in the future would have the potential to be ‘take at home’ drugs with the enhanced market opportunity that entails.

A neuroplastogen approach also takes chemistry into a more diverse universe based on a broader range of targets being enlisted to engender neuroplastic changes, and different ways of engaging the primary targets of psychoplastogen’s. Fewer Neuroplastogen programs are at the clinical stage, but there are many companies active in this space, and likely a whole bunch under stealth mode. The molecular targets for these include 5-HT2A, NMDA, TrkB, mTor, and even direct alteration of neuronal microtubules by targeting Microtubule-Associated-Protein 2 (MAP2) to induce neuroplastic changes relevant to psychiatry through to traumatic injury recovery.

Within the neuroplastogen category you have companies working on molecules that are inspired by psychoplastogen structures such as DLX-159, GM-5022, SPT-348, TSND-201 but are chemically distinct. Other companies are focussed on hybrid molecules and poly-pharmacology, e.g., GM-2505 a 5-HT2A agonist + serotonin releaser, or MDMA + Citalopram combinations. Beyond these you have approaches that are structurally distinct from traditional psychedelics but still focused on their targets and inspired by their neuroplasticity effects. For example, companies are and will target the 5-HT2A receptor using different modes and design molecules that are functionally biased, those that are positive or negative allosteric modulators (e.g., pimavanserin), and probably ago-allosteric molecules along the way.

A comparison to the 5-HT2C receptor is worth contemplating, given that agonists targeting this receptor for obesity (some initially approved, ie. Fenfluramine, Lorcaserin) have fallen away but 5-HT2C agonists are now approved for rare epilepsies (Fintepla) and this has led to a surge in interest in 5-HT2C agonists (e.g., Longboard acquired by Lundbeck, Brightminds) for epilepsy writ large. Companies are also looking to develop 5-HT2C positive allosteric modulators. An allosteric approach to targeting the 5-HT2A receptor (or 5-HT2C) is a worthwhile pursuit given the close homology to the 5-HT2B receptor activation of which is associated with cardiac valvulopathy leading to drugs being removed from the market.

As mentioned above, further along this continuum of innovation you will have novel chemistry directed at completely novel targets, whether targets up or downstream of current targets of interest or new targets predicted to have neuroplastic effects. The diversity of targets will likely increase (i) as we have a greater appreciation that the brain, and CNS more generally, is much more malleable to both pharmacological and non-pharmacological (psychotherapy, bio-neurofeedback, brain-devices, etc) intervention; and (ii) with the use AI, ML and bioinformatic approaches to identify new targets and therefore identify new chemical starting points through in-silico screening which can direct high-throughput screening in drug discovery projects.

Novel targets, novel modes of action, and novel chemistry will provide a plethora of substrate for innovative drug discovery programs, with investment being the rate limiting step – but that is as it should be so only the most robust and validated datasets and rationales are funded.

To end, I’ll throw in another analogy from my book reading interests. The above continuum of innovation brings to my mind Stephen Jay Goulds book ‘Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History’. The book explores the incredibly well-preserved 530-million-year-old fossils at the Burgess Shale in the Canadian Rockies. The fossils show that animal life was abundant, diverse and innovative in evolutionary approach, with many not progressing due to chance or contingent factors, or specific traits being co-opted fortuitously at later points in evolution. As with innovation in drug discovery and development – its not linear.